Interconnection is an increasingly vital implement in reaching net zero both in the UK and globally. By connecting the electricity systems of neighbouring countries, interconnectors (undersea high-voltage cables) can provide essential services including grid balancing by importing electricity during periods of high demand and low supply and exporting in the reverse scenario.

As the UK continues its role in global decarbonisation, our electricity network will become increasingly reliant on more intermittent forms of electricity generation, predominantly renewables such as solar and wind.

This change has already been sealed from a regulatory perspective, through the UK’s net zero by 2050 commitment; it is now a question of developing an electricity network that will be fit for purpose.

Although there are multiple technologies that can help balance the intermittent nature of renewables, such as battery energy storage systems (BESS), the value of interconnectors is drawn from their ability to transport larger volumes of electricity overseas.

The UK’s interconnections

Having historically been a disconnected island from an energy standpoint, the UK has formed six new international connections in just over a decade.

As of December 2023, the UK boosts nine interconnections; these are:

| Interconnector name | Connecting country | Capacity (MW) | Year commissioned |

| IFA | France | 2,000 | 1986 |

| North-South | Republic of Ireland | 540 | 1995 |

| Moyle | Domestic | 500 | 2001 |

| BritNed | Netherlands | 1,000 | 2011 |

| East-West | Republic of Ireland | 500 | 2012 |

| Nemo Link | Belgium | 1,000 | 2019 |

| IFA 2 | France | 1,000 | 2021 |

| North Sea Link | Norway | 1,400 | 2021 |

| Viking Link | Denmark | 1,400 | 2023 |

The latest edition, Viking Link, is also the world’s longest onshore and subsea interconnector, according to National Grid.

Costing £1.7 billion, the UK-Denmark link stretches for 475 miles under land and sea, joining the Bicker Fen substation in Lincolnshire with the Revsing substation in southern Jutland, Denmark. Although the interconnector is currently running at a reduced capacity of 800MW, this will gradually increase to its peak of 1.4GW over 2024.

This is the National Grid’s sixth interconnector, which began development in 2019 and was completed in December 2023. National Grid operates the majority of the UK’s interconnectors including IFA, IFA2, BritNed, Nemo Link and North Sea Link.

The rapidly-expanding interconnector network has meant that the UK’s interconnector capacity has more than trebled since 2010, from 2,540MW to 8,240MW today, and is expected to increase to 8,840MW at the end of 2024, by which time Viking Link will be operating at full capacity.

Importer to exporter

Britain held the steady status of importer of energy for the decade prior to 2022 before swinging in 2022 to becoming a net exporter for the first time in 44 years.

This meant Britain broke away from its import average, which hovered at roughly 5% for the preceding decade, as illustrated by the UK Energy Research Centre’s (UKERC) graph featured below.

Cumulative sum of GB net electrical imports per year

According to the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) it was France’s interconnectors that fuelled a significant portion of this change.

France’s gas supply was impacted in 2022 due to stress corrosion making nuclear units unsafe, which led to a number of assets being switched off whilst assessments were taken, decreasing the country’s domestic supply and thereby increasing its need for British imports.

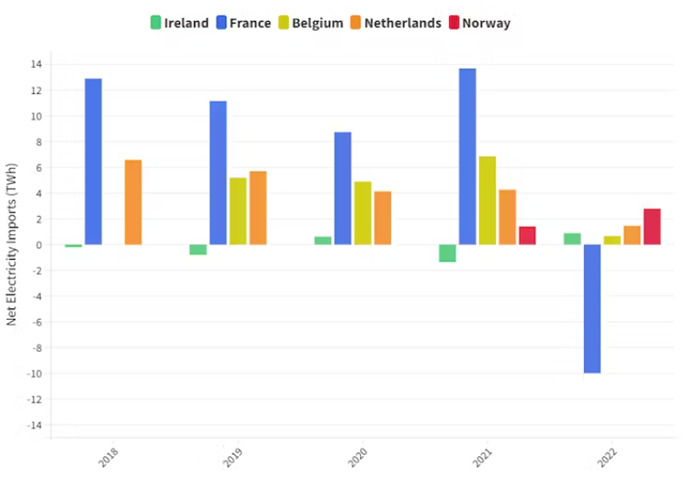

UKERC revealed that net imports to France from Britain in 2022 were 10TWh, a complete switch from 2021, which saw 14TWh of net imports from France to Britain.

Net GB imports by country 2018-2022 (TWh)

“This is an enormous swing of 24TWh from a single point of connection, and represents the largest annual change in a single electricity source since the shift from coal to gas in 2015/16,” wrote authors Joseph Day, postdoctoral research assistant in energy informatics; Geraint Phillips, PhD student; and Grant Wilson, lecturer at University of Birmingham, in an article for the UKERC.

“To put 24TWh in context, this is broadly similar to the amount of electricity Scotland uses each year, or the annual output from Britain’s onshore wind generation.”

The development of the nuclear situation in France led market researcher Cornwall Insight to update its Power Market Outlook to account for increased interconnector exports from Britain to France to continue into the late 2020s, a reversal from the previous norm.

Connecting to net zero

As Britain’s electricity network reduces its reliance on fossil fuels, interconnectors will be pivotal in ensuring the nation’s energy security by sharing power across markets.

An illustration of this relationship can be seen in National Grid ESO’s daily electricity mix statistics for January 2024, which show decreasing fossil fuel input coinciding with increased imports.

GB electricity mix January 2024

In its Energy White Paper published December 2020, the UK government announced it aims to have a minimum of 18GW in interconnection capacity by 2030, which will require an additional 9.16GW added in the next six years.

This target saw a severe setback in March 2023, when the Norwegian government refused the application for a proposed 1.4GW, 650km interconnector between Norway and Scotland, which would have included a joint venture between Norwegian companies Lyse, Agder Energi, Hafslund E-Co and Vattenfall.

Despite this, the UK remains in conversations around future interconnector projects, including a 700MW Northern Ireland-Scotland interconnector project dubbed LirlC, as well as the UK-Netherlands LionLink 1.8GW interconnector, which began construction in April 2023.

One of the most exciting interconnection projects in the market comes from developer Xlinks, proposing a 10.5GW Morocco-UK connection supported by four 3,800km High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) sub-sea cables between a solar and wind project in Morocco’s Guelmim Oued Noun region and Alverdiscott near the north coast of Devon, England.

Although still in the development stage, if built, the proposed Xlinks project will be five times longer than Viking Link.

There are also a number of renewable energy agreements aimed at increasing interconnector capacity including a UK-Ireland agreement and one between the UK and Germany.