By the end of 2024, the UK will have 18% of the estimated 85GW of global offshore wind capacity. If it meets its current growth plans, it will remain the second-biggest offshore wind generator globally until 2030.

That is according to the Offshore Wind Insight – May 2024 report, published by Offshore Energies UK (OEUK), which details the UK’s transition to the use of wind as a primary green electricity source. The report outlines targets to reach 50GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and assesses the UK’s supply chain readiness to support this growth.

Renewable energy sources make up an increasing amount of the UK’s energy mix; wind generated more electricity than gas in the fourth quarter of 2023 for the first time. The UK remains a net energy importer for the foreseeable future, but electricity often meets a tenth of total GB power demand.

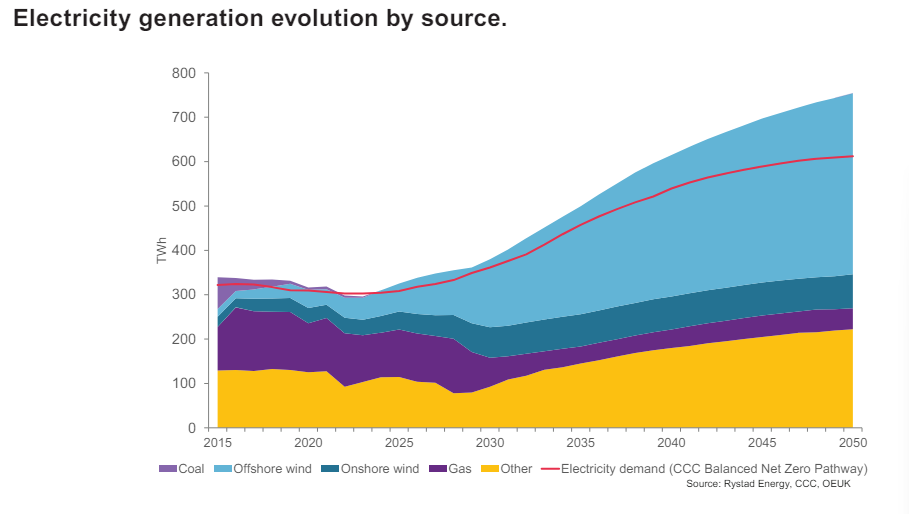

Wind power represents around 30% of total UK electricity generation, as shown in the graph above, but there is uncertainty around the UK’s ability to deliver on its ambitions for offshore wind deployment.

Projected wind generation does not come close to meeting the UK’s targets. The report references recent challenges, such as cost inflation, prolonged consenting timelines and supply-chain pressures, which make it more uncertain that the targets will be met. These things will take time to address, and substantial investment is needed.

The UK has enough projects in the pipeline to meet its 50GW by 2030 target, of which floating wind is expected to contribute 5GW, but they are moving too slowly; the current timeline between lease and operation is around ten years.

Finance and supply chain

Spending on offshore wind is now at about £7.7bn/year and projected to rise to £15bn/year by 2030 and – potentially – £29bn/year by 2035. The report cites the Industry Growth Plan estimation that the UK will benefit from wind development by as much as £25bn.

OEUK advocates that the UK’s review of electricity market arrangements (REMA) should account for wind and solar becoming “the backbone of UK power supply”. Specifically, the “race to the bottom” caused by the Contracts for Difference (CfD) process, coupled with recent inflation, has squeezed margins and put pressure on supply chain finances.

According to the report, CfDs will not necessarily remain the primary funding mechanism over a longer time frame. An alternative route to finance for wind developers is the power purchase agreement (PPA), which might become increasingly popular as PPA prices are expected to exceed CfD rates in the coming years.

The CfD has been very effective at bringing new technology to market but has “squeezed the supply chain to the point where it can hardly reinvest”.

Crucially, the report says that floating wind could be a “game-changer” for the UK supply chain. This is an opportunity for the UK to build a “truly home-grown supply chain,” but “an ambitious and cohesive approach is required”.

The existing supply chain is “much better” positioned to capture market share in floating wind than it has been for fixed. Existing expertise in subsea engineering and technology, deep water operations and floating structures should help position the UK as a leader in the floating wind market