Industry leaders from Shell, the Crown Estate, Simply Blue, Arup and Siemens Energy discussed the ‘growing pains’ of offshore wind in a session at All Energy Glasgow this week.

Offshore wind provides another important piece of the net zero equation, allowing the generation of energy in deeper waters where wind speeds are higher. However, as with most renewable technologies, scaling up supply chains requires significant investment and planning.

Charlene Leppard, supply chain manager of ScotWind Projects at Shell, said that “within the UK, we’re currently focused on floating offshore wind, because that really draws to our experience and our history in offshore engineering in oil and gas”.

“In March last year, we signaled our intent to play a leading role in the UK energy transition by advising that we’re going to invest up to 25 billion in the UK over the next decade subject to of course, are board approvals. 75% of that would be invested in low carbon and zero carbon projects,” Leppard said.

Last year, ScottishPower and Shell signed agreements with Crown Estate Scotland to reserve the seabed rights for their MarramWind and CampionWind floating offshore windfarms, which will have a combined capacity of 5GW.

Leppard identified early investment in port infrastructure and improving supply chain capabilities as key to the development of Shell’s floating wind projects. “It’s really clear to see there’s a significant amount of investment that’s required around Scotland in the UK to deliver these sorts of projects. So the port’s infrastructure and supply chain are going to be critical for us as we move forward,” Leppard said.

Tim Stiven of the Crown Estate said that his role was “to create market offers of seabed leasing to offshore wind developers, which are really attractive in a global context to make sure that we secure the best cohort of the world’s leading developers to come and invest in the UK.”

Stiven said that “my basic take on this is that the role the Crown Estate can most helpfully play is to create a market environment for that bit that were responsible for shaping of managed and well-defined risks.” The Crown Estate is about to launch a commercial leasing round in the Celtic Sea for up to 4GW of floating wind, Stiven said, with 400MW of floating wind projected to be in operation before 2030.

This process of leasing and engagement between developers and infrastructure like ports provided early pilot projects which the Crown Estate was learning from which gave “an understanding of the requirements on both sides and a building of trust and engagement, which I think is essential.”

“Our leasing process will allow developers to build in phases and to consent their projects and phases and therefore, essentially match the pace of their development to the capacity and capability of the supply chain,” Stiven said.

Putting environmental regulatory processes upfront before leasing would help bring a stronger set of projects to market and give developers more information about risks, while the Crown Estate would also invest in “a range of pre consent surveys for engineering and environment” to “place vital data in the hands of developers”.

Work on floating wind had to be done in partnership with the Electricity System Operator in order to ensure compatibility between offshore spatial design and the technical design for onshore and offshore grid infrastructure upgrades.

Stiven said he was pleased about the launch of the Floating Offshore Wind Task Force in 2022 which brought together government, developers and the supply chain. The task force found that many new ports and floating substructure manufacturing facilities, and “pointed out the essential link between the proximity of port infrastructure to project sites”.

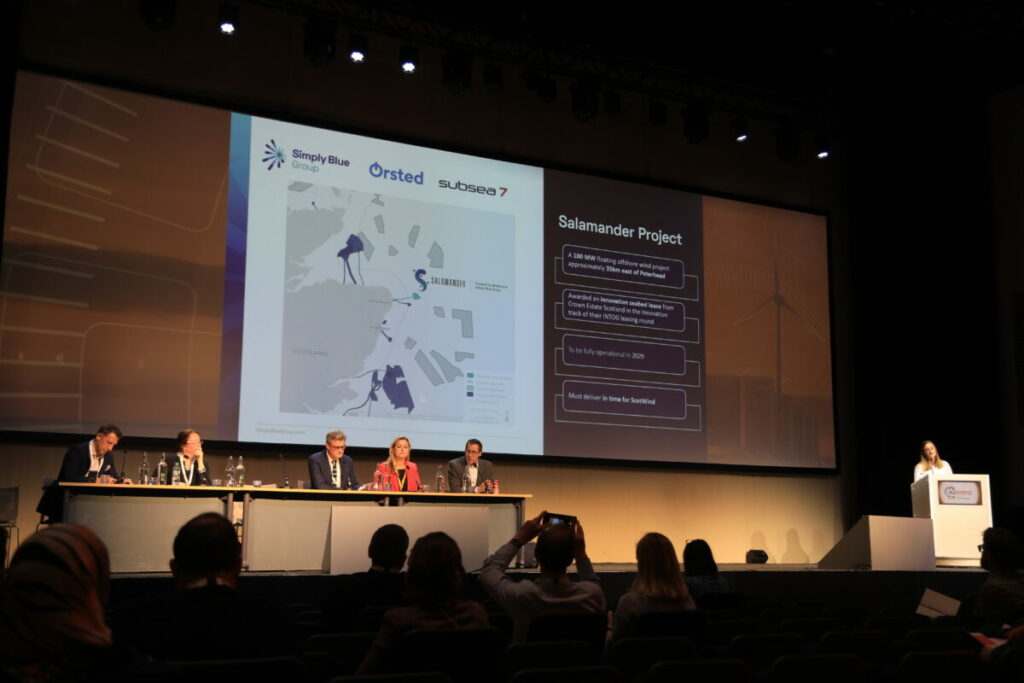

Charlotte Cochrane, stakeholder engagement manager for the Salamander Project at Simply Blue, gave an overview of “how projects like ours act as stepping stones and can help to ease some of the growing pains of floating offshore wind.”

Simply Blue is a “very early stage blue economy project developer”, with “a portfolio of over 10 gigawatts under development at the moment”, including the Salamander project and the Blue Gem Wind project, among 14 UK projects.”

Salamander is a 100MW floating offshore wind project off the coast of Peterhead in the North Sea. It’s been awarded an innovation seabed lease by Crown Estate Scotland, and is projected to be operational by 2029.

Cochrane said the biggest challenge was in “breaking new ground”, with “certain elements of novelty across our supply chain”. Although the new floating technology has enabled projects further offshore, the supply bases serving fixed offshore wind are no longer really the best place to service a full time project. So what that means is, it’s kind of been dragged towards more remote, more fragile coastal communities that haven’t been as well developed and had the same level of investment. And that has led to something or is leading to something of a supply gap. And similarly, an infrastructure gap,” Cochrane said.

This means that supply chains need to be developed with investment to meet the “upcoming deployment step change”, which Simply Blue is addressing by making supply chain development a focus of their project development approach. “We scale up our projects as the supply chain scales up, and we also support that scale up as well. Our projects act as a sort of catalyst to stimulate that supply chain activity paid on the gigawatt scale timelines. You know, if a wait till gigawatt scale, it’s too late, we wouldn’t have a supply chain there.”

Cochrane underlined the need for small scale, small risk projects to prove the technology, “continuous early engagement, bringing the supply chain and the wider community along with at every stage of the project.” This engagement highlighted a deficit of welders at one project in Scotland, which is only going to get worse, Cochrane said, because less than 20% of welders are under 35.

To combat this, companies need to engage with local communities, encourage STEM training and apprenticeships, and work with legacy oil and gas organisations to retrain. Simply Blue is working with the National Decommissioning Centre and the Net Zero Technology Centre in Aberdeen to adapt the simulator they used for oil and gas engineering to simulate the Salamander project.

Borbala Trifunovics, director for ports and maritime for Arup said that there are still a wide variety of floating wind platform typologies and “over 50 technology providers who are working on those technologies. So there’s a huge envelope of uncertainty around What solutions can be used and what they look like how big they are, what materials they are”. These all require “quite different logistical and deployment solutions to those that we are comfortable within the fixed wind realm”.

These technologies require “a deeper integration and commissioning berth and that’s one of the major challenges UK ports have at the moment, they don’t have those deep berths with large onshore storage.”

Trifunovics said that the ambition for floating wind – 5GW by 2030 with nearly 20GW potential pipeline – is very ambitious, but “the supply chain just isn’t ready to cater for that yet”. She warned against simply importing key parts of the supply chain like substructures, which should be challenged with either “tariffs, or looking at a building in the increase in transportation costs, or carbon offsetting around importing in from international supply bases.”

“Critical investment is needed into UK ports to build floating offshore wind,” Trifunovics said, which required a “national view” to deliver commercial scale floating wind.

Lastly, Andrew Elmes, head of business development (Wind), at Siemens Energy, said he was there to represent the supply chain, which Siemens has a lot of experience in with 21GW of global installed wind capacity and 8GW in the UK.

On the different technologies available, Elmes said “It is about looking at some of these foundation structures and either picking the VHS versus Betamax but also seeing that all of them are going to have their contribution.” Out of the 100 or so foundation concepts that Siemens is testing, “maybe five to 10 of those could survive. So we’re not seeing a single technology that would rule,” Elmes said.

These proof of concepts would continue “up to about 2025… and only into that last five years of the decade we’re going to see the early commercial projects. But then in the 2030s in our assessment it really does come of age,” Elmes said.

In an industry where things are changing quickly, floating offshore wind is right at the beginning of its development cycle, with the associated risks and possibilities that come with emerging technologies.

The possibilities for using existing oil and gas infrastructure and supply chains are obvious, but ports that are designed to produced fixed offshore wind will need significant development and investment to make them capable of handling floating wind supply chains. How quickly these new technologies can be deployed relies on many moving factors, but the potential and possibilities are undoubtedly exiting.

Current-News publisher Solar Media is hosting the third edition of its Wind Power Finance & Investment Summit Europe in London this 19-20 September. The conference will focus on investment strategies, alleviating bottlenecks, and which countries and technologies are the most exciting ahead as the industry sets to expand to help reach 2030 targets. Packed with industry leaders representing financiers, investors, developers, government departments and more this is the leading conference for decision makers in the European wind industry. More information, including how to attend, can be read here.