The importance of interconnectors in the UK’s future net zero ambitions cannot be overstated. As explored in a February 2024 Current± blog, increased interconnection between nations is vital to ensure grids can remain balanced despite the fluctuating nature of renewable energy generation. Several interconnector projects have recently been greenlit; in March 2024, UK energy regulator Ofgem recommended two high-voltage interconnector projects between the UK and Europe be approved, with these having a total transmission capacity of 3.2GW.

Despite the uptick in interconnection projects connecting the UK to mainland Europe, one project has faced significant hurdles. The Aquind Interconnector, a proposed interconnector between the south of England and France, has been the subject of local backlash, political controversy, and even objections from the Royal Navy.

The plans

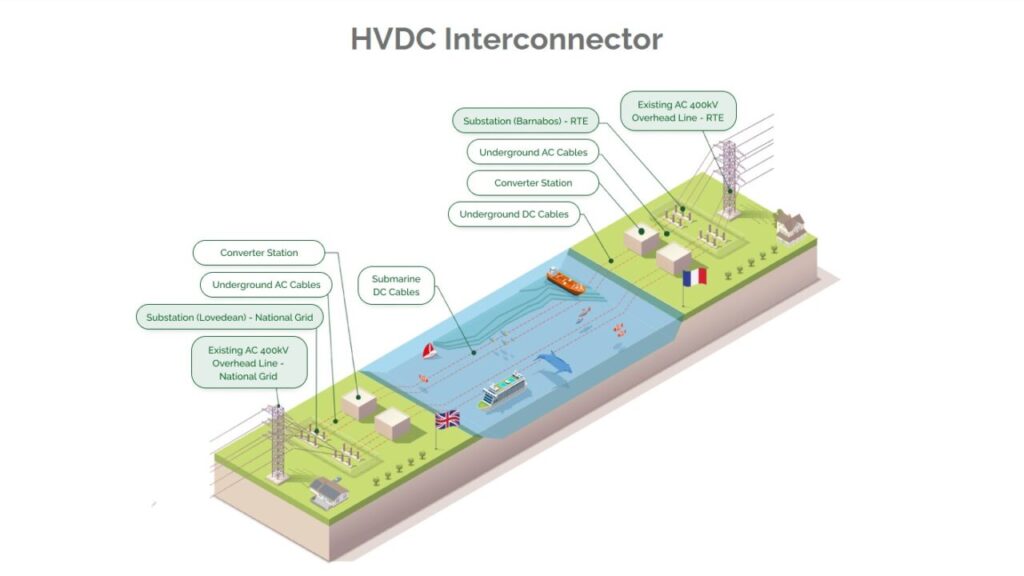

The Aquind Interconnector is a major energy infrastructure project aimed at improving electricity supply between the UK and France. It involves the construction of a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) subsea power cable, spanning approximately 238 km across the English Channel. It will have a capacity of 2GW, with an annual energy transmission capacity of around 17TWh, which is equivalent to around 5% of the UK’s total consumption and 3% of France’s total consumption.

The subsea cables will run from Lovedean, near Portsmouth in the UK, to Barnabos in Normandy, France, and the project is expected to cost around £1.35 billion. The cabling will connect to newly built converter stations on each side of the Channel before running to substations run by National Grid on the UK side and RTE in France. Following this, the project will connect to existing AC 400kV overhead transmission lines, once again run by National Grid and RTE.

History of the development

The Aquind interconnector has been under development since late 2019, with the first requests for a Development Consent Order (DCO) being submitted to the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) in November 2019. In November 2022, Aquind director Richard Glasspool decried the glacial pace of the consenting process in a press release on the project’s website, stating “consent regimes have evolved into a labyrinth that discourages anyone from developing major energy transition infrastructure. Many energy projects besides Aquind Interconnector have been affected by ever-extending DCO timelines.”

The project was initially denied planning permission in January 2022 by then-business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng, who refused permission as he did not believe “more appropriate alternatives to the proposed route” had been given due consideration. However, the decision was overturned by a High Court judicial review just a year later. A final approval decision on the project is expected to be made later this year.

Controversies and the MoD

The project has been subject to intense scrutiny, with a 2021 investigation by The Guardian newspaper revealing that two of the project’s promoters, Viktor Fedotov and Alexander Temerko, had been making substantial donations to the then-ruling Conservative Party. Aquind denied any wrongdoing later that year.

Local campaign group Stop Aquind has been vocal in its opposition to the project since its inception, although a more recent independent survey, carried out by market research firm Savanta, suggested that Portsmouth residents are broadly in support of the project, with only one in five saying that they would be unhappy with any temporary disruption the project would cause.

However, a larger threat to the project’s realisation comes at the hands of the Ministry of Defence (MoD). In August, the MoD penned a letter to DESNZ urging the Secretary of State to halt the project for security reasons, calling the proposed development “a cause of significant concern”

The project would cross into water frequently used by Portsmouth’s naval base, HMNB Portsmouth, which James Muncie, deputy director of the Directorate of Economic Security and Statecraft for the MoD suggests “would unacceptably impede and compromise the safe and effective use of a key defence asset and Royal Navy operations in the area of HMNB Portsmouth and the English Channel, including unacceptably limiting military training”. Muncie went on to call the development “a clear risk to UK defence and national security”.

The cable would cross into an area known as military Danger Area D037, and concerns have also been raised that the project could disturb old munitions disposal sites in the area.

In an attempt to mitigate the MoD’s concerns, Aquind offered to allow the MoD to oversee the development process, but the Ministry did not feel this would overrule their concerns and “does not consider any other sufficient or appropriate mitigation to be available”.

However, this recent statement from the MoD goes against its previous view on the issue; an October 2020 submission from the Ministry to the Planning Inspectorate said the ministry had “no offshore safeguarding concerns with this proposal”, as the “Aquind interconnector cable route runs clear of the main navigation channels used for deploying warships out of HM Naval Base Portsmouth and only a small section of the cable route falls within the port limits”, meaning that it is unlikely that the cable’s route would need to be urgently cleared for deploying of a warship.

It is somewhat unclear why the MoD has changed its position on the development; part of Munice’s open objection letter states that “the reasons why the Proposed Development is a cause of significant concern for the MoD and why MoD considers development consent should be refused necessarily involve information regarding UK defence and national security which it would be contrary to the national interest to disclose”. As such, only high-level government officials will be able to view the full context of the MoD’s sudden objection to the project.

In response to this, Ben Iorio, a spokesperson for Aquind, said: “Aquind strongly dismisses the unsubstantiated position of the MoD that Aquind Interconnector would unacceptably impact HMNB Portsmouth. This stance marks a complete reversal from the MoD’s previous position during the 2020 examination.”

When Current± reached out, Aquind did not respond to requests for comment. The UK government has also not provided significant further comment on the issue, merely stating: “The re-determination process remains ongoing, and submissions have been provided by the Ministry of Defence as part of that work.”

IFA2 and the differences

Since the MoD began raising objections, Aquind has alleged unfair treatment around its project, noting that other similar interconnector projects across the Channel have gone through the approval process without encountering security concerns.

One of these, the IFA2 interconnector, is an interesting point of comparison to Aquind’s project. The project moved through the planning process with relative ease, despite making landfall near Portsmouth and other naval operations, with the Royal Navy even sending guarding ships to protect the cable during the laying process.

On this, Iorio noted: “The technology and installation methodology for Aquind Interconnector align with other operational interconnectors in the English Channel, like IFA2, which crosses directly in front of Portsmouth Harbour without security concerns. The MoD raised no issues with these projects, or with nearby offshore wind farms.”

Given the size and scale of HMNB Portsmouth – the naval base plays host to over half of the Royal Navy’s surface ships, as well as its Type 45 destroyers, two flagship aircraft carriers, and mine countermeasures vessels – it isn’t unreasonable to see that the Navy may want to limit sea-based development work in the area.

It could be argued that the combined presence of the IFA2 interconnector and the Aquind interconnector could have posed a national security threat, and that Aquind was simply unlucky in being a later applicant to the area; however, without further clarification from the MoD, all suggestions as to why the project was rejected remain purely speculative.

The fate of the Aquind Interconnector remains uncertain, caught between the need for increased energy interconnection to support the UK’s net zero ambitions and the rising concerns over national security. The MoD’s change of course and the lack of transparency surrounding its objections have only heightened tensions. As other interconnector projects proceed without similar hurdles, Aquind’s fate may ultimately hinge on whether the government prioritises energy security or national security concerns in this case.