Today the UK’s Committee on Climate Change has recommended that the UK eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from its economy by 2050, in a move which would have significant repercussions on its energy system.

With a four-fold increase in low carbon power, a doubling in electricity demand and a much more ambitious electric vehicle revolution than is already on the cards, the committee’s report paints a picture of an energy system entirely different to today’s.

The rise and rise of low carbon generation

Such widespread electrification will require significant quantities of power, all of which will need to be low carbon. And the figures cited by the committee illustrate the scale of change required.

By 2050, the CCC’s modelling shows that a doubling of total electricity generation capacity will be necessary for the UK to transition towards a net zero economy which, in turn, would need four-times as much low carbon power output compared to today.

That equates to a leap from the 155TWh of low-carbon generation on the grid today, to between 540 and 645TWh by 2050, illustrating the gap between the committee’s ‘Core’ and ‘Further Ambition’ scenarios respectively.

That wide-scale deployment of low carbon power, and especially renewables, will need to start in the early 2020s if, as is necessary, all power generation will originate from low carbon sources by 2050. This will start with the coal-phase out in 2025, with carbon capture and storage now deemed pivotal to the power sector’s ongoing decarbonisation. The 2030s and 2040s will see continued expansion of renewables and a decarbonisation of peak power generation, stemming from the development of hydrogen as a fuel for these plants.

While the committee has not put forward any prospective generation mix, the report argues that as much as 75GW of offshore wind power could be deployed by 2050, a seismic leap from the 8GW currently installed today.

Speaking on the subject, CCC chairman Lord Deben explained that while the net zero target doesn’t prescribe a technology mix, the committee would expect the cheapest options – wind and solar – to do the “heavily lifting”.

“We’ve cautiously assumed that variable renewables provide no more than 60% of generation, that is still more than the entire size of the power sector today, but we are clear that if flexibility can improve sufficiently for them to provide a greater share then that is likely to be desirable,” he added.

Cost is an important factor in this equation. Forecasts included in the CCC’s working demonstrate a continued cost decline in renewables to such an extent that solar PV in particular comes to the fore, with a levelised cost of electricity as cheap as £41/MWh by 2050. Offshore wind, for comparison, is expected to slide from £69/MWh in 2025 to just £51/MWh by 2050.

Those costs are equivalent to renewable technologies being able to deploy without the need for subsidies, but the CCC has once again set out its stall in calling for government intervention to secure a route to market for established technologies.

Subsidies have proven to be politically contentious given their contribution to consumer bills, and the CCC expects the cost of low carbon policies attached to consumer bills to continue to climb. Those levies are expected to rise from the current £7 billion to around £12 billion by 2030, before falling as legacy contracts expire. A notional cost of £4 billion per year is expected to continue beyond 2050.

The CCC is however once again quick to state how the cost of low carbon policies has been more than offset by energy efficiency improvements as it stands, and there’s greater improvements yet to come.

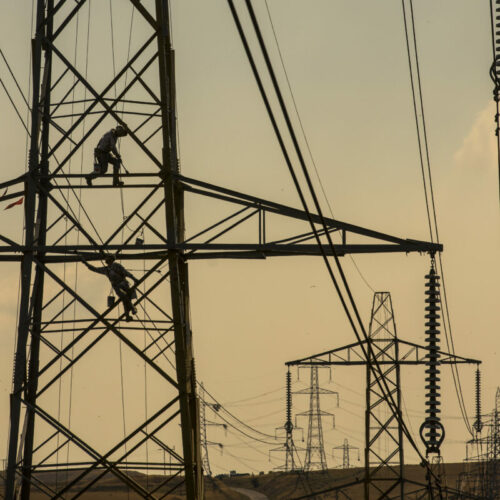

Grids and networks

All of that added power will, of course, need to be transmitted and distributed by some means, and the committee is expecting a a rapid expansion of electricity infrastructure to cater for demand, an investment and deployment initiative which is expected to run throughout the next 30 years.

When it comes to grids and networks however, the CCC has more advice than expectation. It stresses the absolute need to upgrade networks in a timely and future-proofed fashion, ensuring that there is no need to expand network capacities again prior to 2050, in order to protect consumers from extra costs.

A “relatively large” expansion in network capacity, the committee says, is likely to be a low regret option for the country.

Flexibility technologies will also play a crucial role, not just in offsetting at least some of the need for network reinforcements, but in helping the system cope during demand peaks.

Once again however the CCC is mindful to stress that political leadership in this field is pivotal. The government must work in partnership with the National Infrastructure Commission to consider how best the necessary infrastructure can be identified, financed and delivered, with regional coordination also necessary for matters, such as transport, where powers are devolved.

When combined with generation, the committee has suggested that annual investment in the UK’s power sector will need to double from the £10 billion per year figure recorded between 2013 – 2017, to £20 billion per year, figures which only lend greater emphasis to the need for government to design policies with investors in mind.

Driving EVs forward

Alongside heat, transport has always been an aware of weakness for the government’s claims to lead the international stage in carbon reductions. More than ten years on from the Climate Change Act’s ascension and transport emissions have yet to experience anything like the reductions witnessed in the power sector.

That could all be about to change with the advent of electric vehicles, however.

If the UK is to stand any chance of meeting a 2050 net zero target, the CCC has said the country’s nascent electric vehicle market must be supported throughout the 2020s in anticipation of a significant adoption of zero emission vehicles beyond that.

This is perhaps why the committee has taken particular umbrage with the government’s current date for a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles. By setting that deadline for 2040, the UK government has failed to match the ambition of other countries like Scotland and Norway.

The CCC has therefore recommended that the phase-out be brought forward to 2035 at the latest, although 2030 has been described as desirable by chief executive Chris Stark.

In fact, the government would provide a net benefit to consumers by setting the date earlier than it has now, according to the CCC’s number crunching. Analysis included in the report shows how the adoption of electric vehicles could cut annual net costs of transport by £5 billion by 2050, a saving which is only strengthened the earlier the ICE phase out date is mandated.

All those electric vehicles will require more comprehensive charging networks however and the CCC has today recommended that as many as 1,200 rapid chargers positioned near major roads, combined with 27,000 public chargers in and around towns, will be necessary by 2030 to support the electrification of road transport.