A research paper carried out by Professor Alex Kemp and Arturo Regaldo at the University of Aberdeen, has found that the increased Energy Profits Levy (EPL) may have a “major negative impact” on post-tax returns for investors in the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS).

The UKCS principally refers to the North Sea where there are substantial resources of oil and gas, for which the UK claims mineral rights.

On 26 May 2022, the UK Government launched the EPL which introduced a 25% windfall tax on oil and gas ring fence profits but maintained an 80% investment allowance.

In last year’s Autumn Statement, chancellor Jeremy Hunt extended and increased the EPL to 35% from January 2023 until 31 March 2028. The investment allowance was also reduced to 29%, unless used for expenditures relating to the decarbonisation of the sector, in which case the investment allowance remains at 80%.

Using a Discounted Cash Glow (DCF) model for three oil fields to represent UKCS assets of recent vintage, Kemp and Regaldo modelled what effect the new EPL will have on investment in the UKCS.

The three fields range from small (which have faster decline rates) to large (which have slower decline rates).

Table 1: Post-tax NPVs (Real @10%) for the three fields by different investment start-up years with Energy Profits Levy.

Using ‘EPL 1’ to refer to the EPL introduced in May 2022 and ‘EPL 2’ to refer to the EPL introduced in January 2023, Table 5 represents post-tax net present value (NPV) of three oil fields under both EPLs.

Table 5 shows that the economic impact is more significant for older projects compared to new ones. This is because projects that began in 2019 can’t claim additional tax relief from the investment allowances for the EPL, the paper explained. Additionally, the new EPL will apply for a larger portion of the project’s timeline.

This, the paper continued, provided incentives for operators to reinvest or incur capital expenditures (such as infill drilling) to claim higher tax relief during Levy periods.

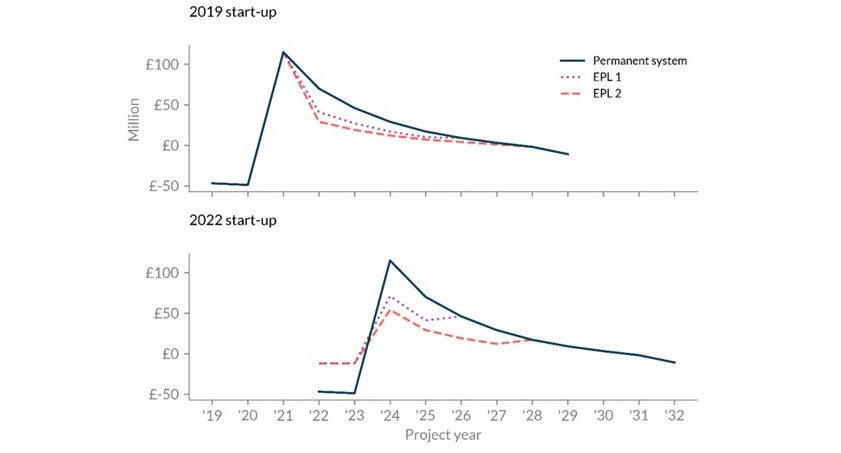

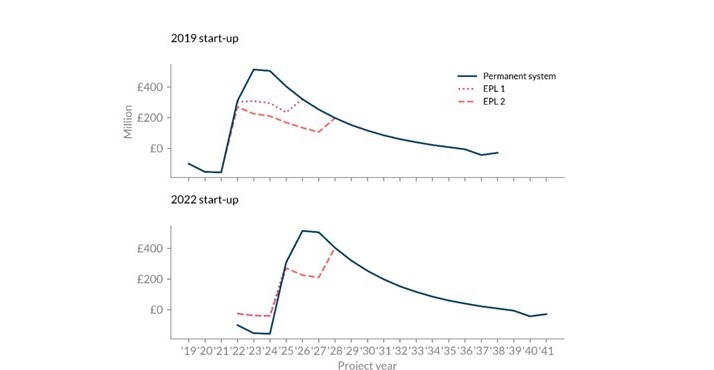

Figures 1 and 2 plot the post-tax net cashflow through time to better understand the comparative effects of both EPLs for small and large fields.

Figure 1: Net post-tax cash flows for the small field by different investment start-up dates assuming tax case where there is other income.

Figure 1 shows that projects that commenced in 2019 experienced higher early net cash flow losses when compared to a 2022 investment start-up. The paper explained that this is due to the 2019 operator being unable to utilise the investment allowances within the EPL; for a 2022 start-up however, its youth means that the post-tax net cashflow is close to zero.

Figure 2: Net post-tax cash flows for the large field by different investment start-up dates assuming tax case where there is other income.

Figure 3 shows that large fields with a 2022 investment start-up were able to achieve tax relief investment expenditures. Profits however, although unaffected by EPL 1 are taxed by the increased EPL 2.

Fields beginning in 2019, on the other hand, were unable to claim tax relief for investment expenditures and would receive early profit taxes under both EPL 1 and EPL 2.

These figures implicate that the timing of investment expenditures and of first production determine the impact of the EPL.

The paper reviewed two behaviours this situation promotes.

The first is that it encourages operators to invest in new projects to claim tax relief immediately, expecting that the EPL will not apply once the project comes online.

The second is that operators phase investment expenditure and productions, taking advantage of the timing of investment reliefs as well as the payments of the EPL.

“In general, it will be easier to delay rather than accelerate investment activity,” summarised the paper.

“The EPL will clearly reduce cash flows and, given the investment allowances from undertaking new investments, there are incentives to delay decommissioning work. This will be the subject of further research.”

Kemp and Regaldo’s research is an interesting point of comparison with the Electricity Generator Levy (EGL) which imposes a 45% windfall tax for “extraordinary returns from low-carbon UK electricity generation” – 10% higher than the increased EPL.

The higher levy for renewable generators met with criticism both within the energy sector and the public.

Displeasure at the disparity between the Levys was heightened as oil and gas giants including BP and Shell recorded record profits last year.

The renewable sector has called for Hunt to “level the playing field with fossil fuels” in the coming Spring Budget.

Current± will post a Spring Budget update upon its release on 15 March.