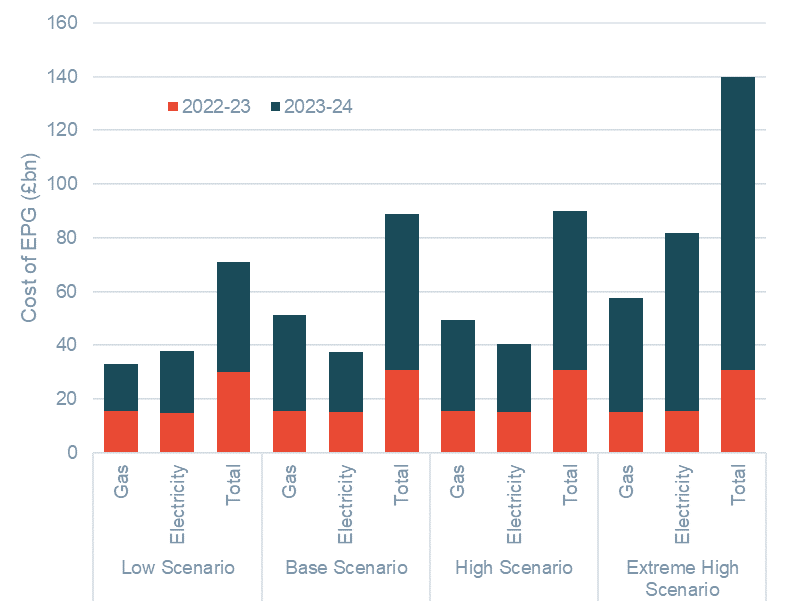

The Energy Price Guarantee announced by Prime Minister Liz Truss as part of a package to help mitigate the UK’s ongoing energy crisis could cost as much as £140 billion.

That’s according to energy market analysis and intelligence group Cornwall Insight, which has forecast the likely cost of the policy over two years. A lower end figure sits at just over half that sum, at £72 billion.

One of the first announcements made during Truss’ term as it began in September, the Guarantee sees the Default Tariff Price Cap frozen at £2,500 for the next two winters from this month, more than a thousand pounds less than the £3,549 cap set by Ofgem.

Introduction of the measure came as a near-doubling of the 4.5 million households in fuel poverty was forecast, with the Ofgem-set cap representing an 80% increase from its summertime level. As reported by this site, the electricity price is now capped at 34p/kWh, gas at 10.3p/kWh, inclusive of VAT.

Cornwall Insight modelled and qualitatively analysed the difference between price levels set by the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) and potential costs for energy consumers over the two years of the scheme.

One thing that stood out more than anything else, according to Cornwall Insight CEO Gareth Miller, was that while the EPG’s costs under the four scenarios modelled were high, was the “significant variation” between the low and high-end forecasts.

“There is nearly £70bn difference between the Low and Extreme High market scenarios. This reflects a febrile wholesale market continuing to be beset by geopolitical instability, sensitivity to demand, weather, and infrastructure resilience,” Miller said, adding that risks grow in the second year as uncertainty increases over time.

Due to uncertainties in commodity markets, there was a chance the government could “get lucky” and be saddled with lower costs, but equally, could go the other way entirely.

“In each case, the government may find itself passengers to circumstances outside its control, having made policy that is a hostage to surprises, events and volatile factors,” Miller said.

“That’s a difficult position to be in.”

Cornwall Insight noted that on top of that, the Energy Bills Support Scheme, worth about £400 per household, will cost at least around £12 billion but is likely to come out higher than that when factoring in additional support that will be offered to the most vulnerable households.

Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng said in late September that the EPG, along with the the Energy Bill Relief Scheme and the Energy Markets Financing Scheme, would cost the country about £60 billion in just their first six months after introduction.

‘EPG should be stopgap rather than long-term fix’

The analysis group recommended that as soon as possible, a viable exit strategy to the EPG be put in place. The scheme should be a stopgap while alternatives are considered, rather than some sort of “final answer” to the impacts of high energy prices, according to the group’s report.

The government aims to fund energy suppliers to cover wholesale energy costs and remove the policy costs of green levies from household energy bills.

Cornwall Insight noted that there are a long list of factors which can come into play to influence the cost of energy: from energy demand and weather to the cost of LNG as Europe looks to restock reserves next summer and many more.

While most of these factors are considered to be out of the government’s control and introducing the EPG to deal with the situation will lower bills and create certainty for households, the EPG will leave the government exposed to global commodity market pricing of electricity and gas.

“The good news is that there is a route through this,” Miller said.

“The government could use the next few months to develop more targeted energy support policies for households, building on proposals brought forward during the late summer across industry actors and think tanks.”

That targeted support could be developed over time and would not need to be migrated to immediately, and policies and schemes could be developed that lower costs overall, over the long-term.

At the same time, ways of reducing energy demand should be explored and implemented, Miller said.

That would not only help reduce costs further but could put the UK into a position to extend support where necessary, “should markets not revert to pre-crisis prices after the two years is up, which is certainly what our fundamental energy price models suggest may happen”.