The Default Tariff Cap (price cap) is an energy pricing mechanism set by the regulator Ofgem to ensure that consumers on default energy tariffs pay prices that are fair and “reflect the cost of energy”.

Initially, the price cap was updated every six months, however in August 2022 Ofgem confirmed it would be updated quarterly. This change was made in anticipation of a volatile energy market following the rise of global prices for fuels such as gas, electricity, and oil from summer 2021, when economies began re-opening after Covid-19 lockdowns.

Ofgem decides the cap level on account of several components:

- Wholesale prices for gas and electricity

- Contracts for Difference (CfD)

- Policy

- Adjustment allowance

- Networks (SoLR)

- Networks (non-SoLR)

- Operating costs

- Payment uplift

- EBIT

- Headroom

- VAT

Ofgem explains the reasoning for the cap being made up of these components being “so that energy suppliers can recover these costs to reduce the risk of them going bust.” However, it does mean that the price cap will mirror the trajectory of the above costs – when these costs increase so will the cap.

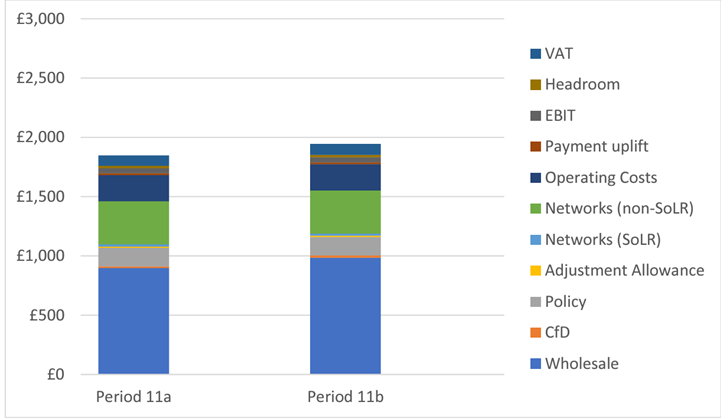

A breakdown of how these components make up the current price cap, which is set at £1,928 until 31 March, can be found below:

Breakdown of Q4 2023 (11a) and Q1 2024 price cap (11b) Energy Price Cap components, direct debit dual fuel

As illustrated above, wholesale prices constitute the largest proportion of the price cap, leaving the mechanism susceptible to wholesale market volatility – a concern that has often been raised within the energy industry.

In this blog, Current± probes the price cap, reviewing how and why the cap levels have changed throughout the energy crisis and examining what place the mechanism has in the UK’s future energy market.

The energy crisis

There is some debate as to the precise beginning of the energy crisis in the UK, but the UK Parliament pinpoints the summer of 2021 following the Covid-19 lockdowns, which saw global gas and electricity prices begin to increase before spiking after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

This saw wholesale gas and electricity prices sky-rocket to record highs, both in the UK and Europe, with levels still hovering way above average pre-crisis levels.

The table below illustrates this spike using yearly average wholesale day-ahead price data from EnAppSys Energy Insight’s ‘Yearly GB Market Summary’ for 2023.

The average day-ahead market price jumped by over 200% between 2020 and 2021, from £35.26/MWh to £118.29/MWh only to almost double between 2021 and 2022 to £204.03/MWh.

The eye-watering day-ahead prices experienced in 2022 – including a high of £354.4/MWh on 23 June – have repeatedly been linked to rising gas prices due to a highly volatile wholesale market driven by uncertainty.

This sparked a debate around the prospect of decoupling energy from the price of gas; an issue the then Prime Minister Boris Johnson weighed in on 25 June, saying: “At the moment, one of the problems is that people are being charged for their electricity prices on the basis of the top marginal gas price, and that is, frankly, ludicrous.”

“We need to get rid of that system. We need to reform our energy markets, as they have done in other European countries.”

Even in 2023, in the context of the Israel-Hamas conflict and Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) strikes in Australia, the average day-ahead price was £94.48/MWh – which although less than half the average of 2022, remains roughly double pre-crisis levels.

With Red Sea strikes in Yemen now also taking place, it appears at least the first half of 2024 will experience similar wholesale gas market volatility at the hands of geopolitical influences.

An inherent susceptibility to geopolitical events

As wholesale prices are the largest contributor to the price cap level, the cap becomes inherently susceptible to geopolitical events, like the circumstances referenced above.

This correlation can be seen by comparing historic price cap levels (below) with yearly day-ahead wholesale price averages (above).

Although the effect of rising power prices was slow in trickling down to the energy price cap between 2020 and 2021, it jumped by over £600 between winter 2021/2022 to Q4 summer 2022 before spiking by over £2,000 between then and Q1 2023, when the price cap reached £4,059 for an average dual fuel household.

The coupling between wholesale energy prices and the price cap has caused concern amongst the energy industry, including the market researcher Cornwall Insight.

Recent predictions for future price cap levels provided by Cornwall Insight are often paired with warnings over the UK’s reliance on LNG and how this is being passed down to consumers.

“The jump in price cap predictions since September has once again highlighted the vulnerability of UK energy prices – and customer bills – to geopolitical events. The Russian invasion of Ukraine demonstrated there is a delicate balance in the global energy market which can easily be disrupted by unexpected events, it looks as though the current situation is repeating that pattern,” said Dr Craig Lowrey, principal consultant at Cornwall Insight, in response to November predictions of 2024 price caps.

Lowrey’s warning was repeated in December 2023, when price cap predictions for Q2 2024 saw a 14% decrease.

Describing the fall in price cap cost predicted by the company as a “small light at the end of the tunnel” for UK households, Lowrey added: “Ultimately, waiting and hoping that we will avoid another global incident that sends energy prices climbing is not a sustainable strategy for the government. To achieve substantial reductions below pre-crisis levels, we must focus on long-term strategies which increase domestic renewable energy sources and reduce our reliance on volatile imports.”

The situation for UK households is exacerbated by the present scarcity of fixed tariff options offered by energy suppliers, as reported by ElectraLink this week, leaving UK citizens, as Lowrey states, “at the mercy of market fluctuations.”

Impact on UK households

Fears over increased price cap levels are expressed primarily on behalf of UK households struggling to cope with record-high energy bills.

During the apex of energy prices, the UK government introduced the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG), in September 2022 capping the maximum amount a UK household could pay for their energy in a year to £2,500.

During its running period from October 2022 to its extended end-date of June 2023, the EPG rate set a standard variable tariff for households paying with standard credit at 35.84p/kWh for electricity and 10.70p/kWh for gas, excluding VAT, from January to March 2023.

The EPG superseded the energy price cap for three consecutive quarters (Q4 2022 to Q2 2023) before it was discontinued for households without prepayment meters from 1 July 2023.

Even though households are paying less under the current cap than they would under EPG levels, energy bills remain stubbornly above pre-crisis levels.

Upon Ofgem’s confirmation of the current cap level late last year, the National Energy Action (NEA) revealed that 6.5 million UK households would be in fuel poverty when the price cap came into force in January 2024.

Ofgem also revealed in December 2023 that energy debt had reached record levels at £3 billion, leading the regulator to propose a one-off price cap adjustment of £16 the Q2 price cap to protect consumers from the “growing risk” of ‘bad debt’.

The future role of the price cap

The impact that increased energy bills are having on UK households has caused members of the industry, as well as energy charity bodies to begin questioning the future role of the price cap.

Similarly, within Ofgem’s November proposal to add a one-off price cap adjustment of £16 to tackle consumer ‘bad debt’, Tim Jarvis, director general for markets at Ofgem that although the price cap was created to protect customers, it remains a “blunt instrument in a changing energy sector.”

In August 2023, the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) released a new report calling for the abolishment of the price cap, as it believed the mechanism had gone “far beyond its intended purpose”.

Although the price was originally intended to protect consumers from price-gouging, The Case Against the Energy Price Cap report revealed that the energy crisis has frozen energy market competition, with all tariffs being priced at or just below the cap for almost two years at the time of the report’s publication.

This, the CPS argued, has mutated the price cap into a “de facto regulated market price” for almost every customer.

Energy suppliers have recently begun re-introducing fixed tariffs, but market options are still more limited than pre-crisis.

The CPS’s concerns were echoed following the release of the Q4 2023 price cap in August which, although revealing a welcome £151 decrease from the Q3 cap, still showed no hint of returning to ‘normal’ levels.

Richard Neudegg, director of regulation at Uswitch.com, said that the price cap “deters suppliers from innovating and delivering better deals,” and suggested reform in the shape of creating a standard tariff “priced fairly, based on costs”.

Simon Oscroft, co-founder of green energy supplier So Energy, commented on the complexity of the price cap’s structure and how this could be causing costs to trickle down to consumers.

“Due to the complex way Ofgem’s quarterly set price cap is calculated, it is loading additional costs from the year on to suppliers in the Q4 price cap period,” said Oscroft.

“This will make it even harder for suppliers to price below the price cap level over the winter [2023/2024], meaning even less opportunity for customers to shop around and find cheaper deals.”

In response to these growing concerns, Ofgem launched a review into standing charges in November 2023, consulting on how they are applied to energy bills, adding that it felt that it was the “right time” to revisit the charge.

The standing charge is included in the price cap and is a location-based daily charge that energy users pay their suppliers to cover the fixed costs of providing gas and electricity, regardless of how much energy is consumed.

Many within the industry said they were “unsurprised” by the review.

Referencing the price cap, a spokesperson from Ofgem told Current±: “It is important to note that, since January 2023, the price cap has fallen from £2,500, under the Government’s Energy Price Guarantee, to £1,928 in January 2024. However, we know that energy prices are still high, due to a combination of sustained high wholesale energy prices, and wider cost of living pressures, which have led to unpaid energy bills.

We are also seeing the return of choice to the market, which is a positive sign and customers could benefit from shopping around with a range of tariffs now available offering the security of a fixed rate or a more flexible deal that tracks below the price cap.

People should weigh up all the information, seek independent advice from trusted sources and consider what is most important for them whether that’s the lowest price or the security of a fixed deal.”